NATURE & FUTURE by Daria de Beauvais

Natura naturans and disfigured nature

Conceived as instances of captivation, Angelika Markul’s works place the viewer at the heart of a dizzying interplay of forces. Nature plays a predominant role, taking the form of an underlying protagonist that is forgotten by the vicissitudes of the present and which, prompted by exceptional circumstance, vents its fury. We witness the power of the elements or the ravages of a form of devastation whose consequences can be seen in medias res on the scale of a landscape or an ecosystem. Nature’s work is a way of reclaiming its mythological right to transform the world.

What Spinoza dubbed natura naturans in the seventeenth century—the agent that makes Nature into its own transformative force—is not only sublimated but also paradoxically magnified by the power of humans who turn against it: natura naturans becomes disfigured nature. The resulting desolation takes a metaphysical turn: Man himself—and the irreversible effects his actions have on the elements—seems to be the plaything of a brooding, powerful force which, on the scale of a planet in a state of constant metamorphosis, redefines the very meaning of the future. Only seeing what seems accusatory in the artist’s approach would be to diminish the meaning of her work: Angelika Markul does not set out merely to denounce rash actions; instead she formulates an aesthetic hypothesis that throws forces beyond our control into sharper relief. This is reflected in the way her films and sculptures relate to one another. The former cannot be seen without the latter, and it is when they are seen in tandem and experienced sensitively by the viewer that, in the classical, Aristotelian sense, they reveal an art form that is an extension of the work of Nature.

The video installation entitled Gorge du diable (2013-2014) [Devil’s Gorge] is emblematic in this regard. The artist captures a natural feature, the Iguaçu Falls, and inflects its meaning by reversing the direction of the flow: the effect is the result of a minimal intervention whose consequences are nonetheless profound. Our gaze is literally drawn in, and we experience a return to an origin we can never quite grasp. This effect would be incomplete if the image, with its ability to “swallow us up”, did not appear alongside a sculptural piece which, because it is motionless, intensifies the petrifying effect of the video. The blackness of the forms and the chaotic way they are arranged recall the residue produced by the crashing waterfall; the viewer finds himself facing not only an unnameable landscape, but also the darker side of his own being. Gorge du diable takes us inside ourselves, as if we were endlessly swallowing all our inner shadows and deepening their impenetrable density. This interplay between an exterior nature that submerges us and the interiorization the artist makes possible is a terrifying confrontation: we each see our cosmic reflection in the mirror held up by the artist.

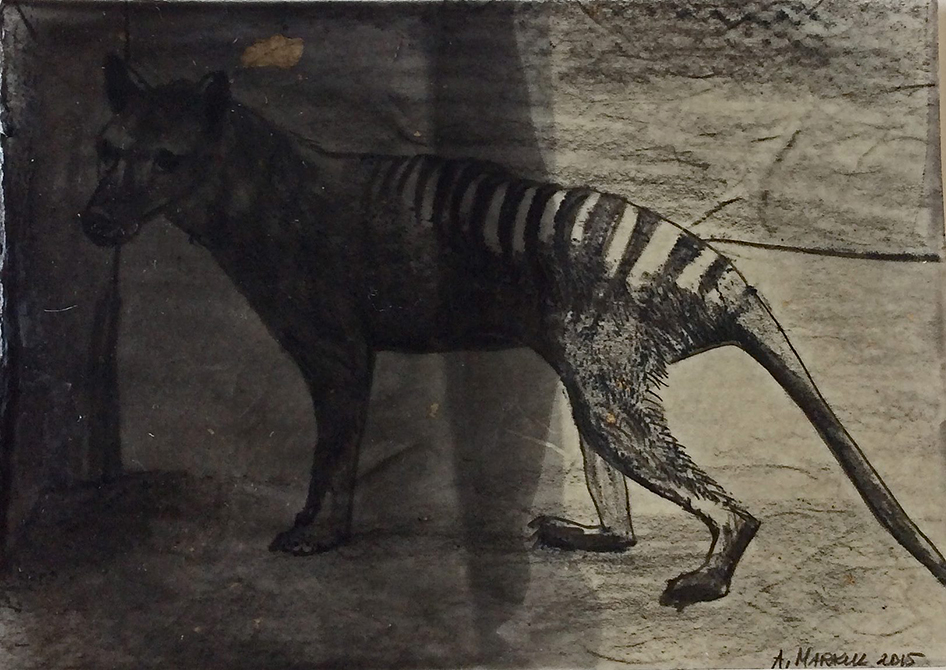

The video installation Bambi à Tchernobyl (2013) [Bambi in Chernobyl] produces a similar sense of confrontation. Contaminated nature (the Chernobyl site filmed in winter by the artist) becomes the focus of a gradual but helpless reclaiming process; in a sense the work involves an exploration of consciousness on the ruined terrain of its own suppressed anxieties. Childhood memory, the nimble grace of an animal or the opening of a flower are no longer signs of renewal; instead we have a complex hybridization between fear and the dying throes of a lost past. Transformations never cease to occur, and persistent traces of the irreversible are like so many stigmata assuming forms that the artist alone renders visible: the forbidden zone of Chernobyl becomes paradigmatic. The focus here is not the 1986 disaster itself, but the way it speaks to us of the bleakest chasms of industrial society, which the viewer can recognize in the innermost reaches of his own body and consciousness. Bambi à Tchernobyl is situated precisely where natura naturans meets disfigured nature. It is a place where the artist exercises her right to draw up an inventory of disasters that ineluctably determine the way we relate to the world.

Between anticipation and the real

This world is not quite our own, and yet not quite another: its contours are neither factual nor entirely imagined. It is a world created by the artist: a scenario of an imagined future that produces its own effects of the real. When the viewer finds himself in front of the installation entitled La Chasse (2012) [The Hunt], there is nothing to indicate the cause of this carnage where hard-to-identify figures seem to have been the victims of both a manhunt and a mudslide. Ultimately what we see is almost a crime scene, and the question is: what made this possible? The same question arises in the series entitled Frozen (2010), where similar-looking, mutant yet strangely familiar animal forms lie in freezers (hi-tech coffins made by a civilization that has mastered the science of cryogenic storage? Sinister larders?). What made this possible? The answer is evident: the artist.

The artist has reverted to the status of a visionary demiurge producing catastrophic situations where we are all invited to formulate our own hypothesis. When the artist presents her “hypotyposes”—to borrow a figure of rhetoric— what she instigates involves both a vestigial trace of something and a warning or premonition. What is to come is already here. Time loops overlap and the immemorial past meets the possible future, changing our entire perception of the present. It’s as if the artist has simultaneously pressed the Fast Forward and Rewind buttons of our consciousness: a feeling of déjà-vu takes hold, and in the oblique glow of a neon light we discover scenes that are unsettlingly strange. The artist’s recurrent use of the most artificial, stark, sometimes blinding light is especially significant. Neon seems anti-natural, and yet what it shines on is a modification of nature that must appear highly familiar to us. Is it in a dream or a fleeting moment of ecstasy that these dark visions appear, haunting the spirit of the viewer like the flash of a neon light searing itself into the retina?

Infiltration of blackness

Angelika Markul succeeds in inventing a landscape which, besides reflecting a fascination with nature, seems to be a landscape of souls. The crepuscular light of the neon tubes reveals a form of art consumed by a kind of contemporary demonology where the “forces of evil” studied by the most illustrious theologians are disconnected from purely religious preoccupations. The artist reveals a constant infiltration of blackness where ghosts are extremely real, where forms are enhanced by technological artifice that makes them all the more chilling. The benefit of such a vision is not so much salvation as a resting place: one of the effects of Pièce du silence (2013) [Room of Silence] is to allow us to take a break from the chaos that surrounds us.

What silence allows is either non-articulated, or it is a scream. Sentences are no longer possible: we can only gasp for breath as we are smothered. Now doubt arises: is what breathes still human? Is it, as in 400 milliards de planètes (2013) [400 Billion Planets], an unresolved ambiguity between the cosmological and the mechanical? Angelika Markul grasps reality at both ends: on the one hand we have cold technology, on the other, formless matter. Between the two, she submits the viewer to a series of ordeals that put our visual and mental resilience to the test. Angst becomes a stationary state, in suspense before the final plunge into the soul and into consciousness.

Daria de Beauvais is curator at the Palais de Tokyo. She curated the first major solo show of Angelika Markul’s work in France, “Terre de départ” [Land of Departure], and also works as a freelance exhibition curator.

This text has been published for Angelika Markul’s solo show “Terre de Départ” at Palais de Tokyo in 201